Reflation trade

Since the election of President Trump, financial markets have begun to price in significant tax cuts and infrastructure spending for the US economy. In addition, there is the belief the economy is operating near capacity. Combined, these two factors further the belief that inflation is on the way, because employers will need to pay more for workers as the labour market becomes tight.

The impact on financial markets has been to sell income (bonds) and buy growth (equities). Many now claim the 30-year bond ‘bull’ cycle is now over.

We have seen this movie before

The extraordinary effort by Central Banks around the world to stimulate their economies, including negative interest rates and quantitative easing, led many to predict a surge in inflation. Bond yields rose to reflect these expectations.

These expectations have their genesis in the monetarist view that more money chasing the same number of goods and services will increase the price of those goods and services.

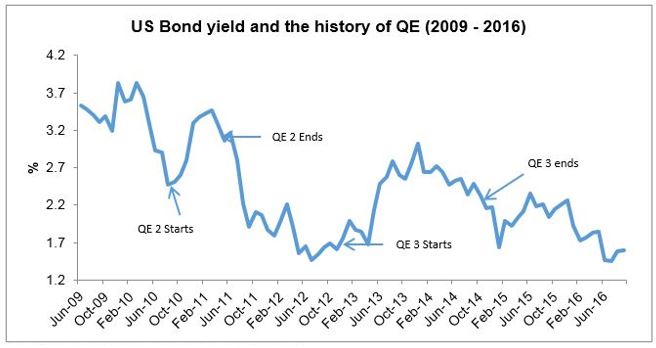

As the chart below highlights – for each time US bond yields spiked to reflect inflation expectations (due to Quantitative easing or so called “money printing”), yields soon rallied thereafter. The expectations proved incorrect. Will it be different this time?

There is still slack in the US economy

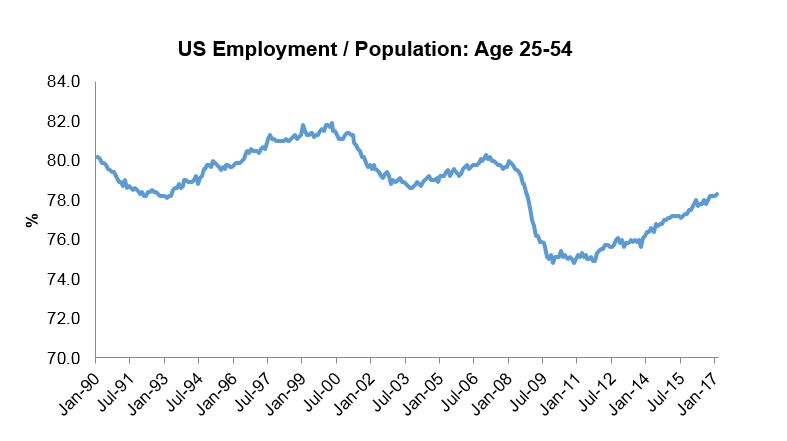

One of the risks to the reflation trade is that there is still some slack in the US economy. While the unemployment rate is quite low at 4.7%, this in turn reflects a low participation rate. While the low participation rate partially reflects aging demographics, it doesn’t explain everything. The employment ratio of the 25-55 aged cohort (the most likely working age group) still remains below the prior cycle.

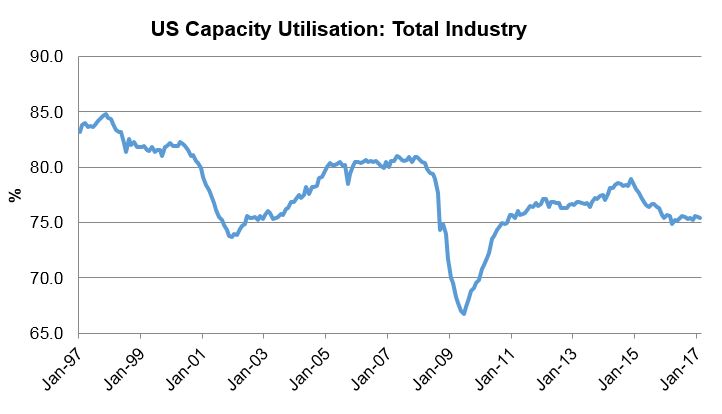

In addition to below cycle participation rates, capacity utilisation remains well below prior cycles, which poses the question: is the US economy really capacity constrained?

Predicting inflation is hard

The Wall Street Journal ran a piece last month suggesting the modern economic tools used to predict inflation have proven to be inadequate. It reported that “five top economists presented a paper at a monetary-policy conference saying the main gauges policy makers typically use to understand inflation – such as "slack" in the labour market – don't actually explain it”. It also found little connection between expectations of future inflation and what prices actually may turn out to be. The paper cited numerous other factors that need to be considered, including:

-

the price of commodities;

- demand may play a small role indeed in fuelling inflation. Research finds that businesses rarely price their products based on how much they are able to sell. Rather, companies pass on to consumers as much of their costs as competition will allow;

- wages aren't negotiated in the smooth manner economists imagine, because power dynamics between employers and employees can shift. A globalised workforce, weaker unions and changing government policy likely play strong roles in keeping prices down;

- paying closer attention to indicators like corporate margins and the amount of industry concentration; and

- fatter profits allow companies to respond to rising commodity and labour costs without increasing prices

Rising wages does not equal rising inflation

The final point above resonates the most with us. Back in January 2015, we wrote a paper: The search for yield: Cyclical or structural?

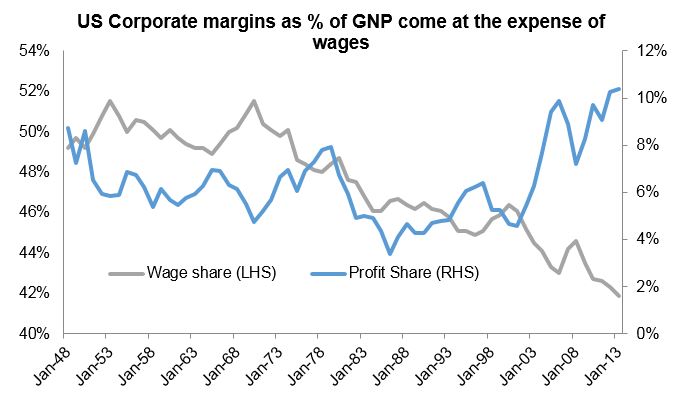

In that paper, we published the chart below, highlighting the shift between corporate profits and wages. Our observation was if rising corporate profits are not inflationary, why do we assume rising wages are? The real risk is that rising wages (if it happens) will come at the expense of profit margins – especially considering they are at already very high levels.

If this was indeed the outcome, the implications are very bullish for bonds and devastating for equities and also very much not with consensus. And being very much non-consensus, the speed of unwind could be rapid.

Central Bank track records are not great

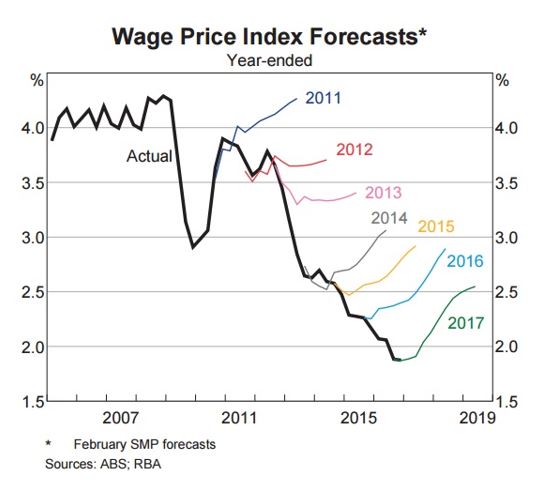

Market participants regularly turn to Central Banks for guidance on future monetary policy. However, this is generally fraught with danger. Central Banks have been notoriously poor at predicting inflation (see RBA chart on wage growth expectations).

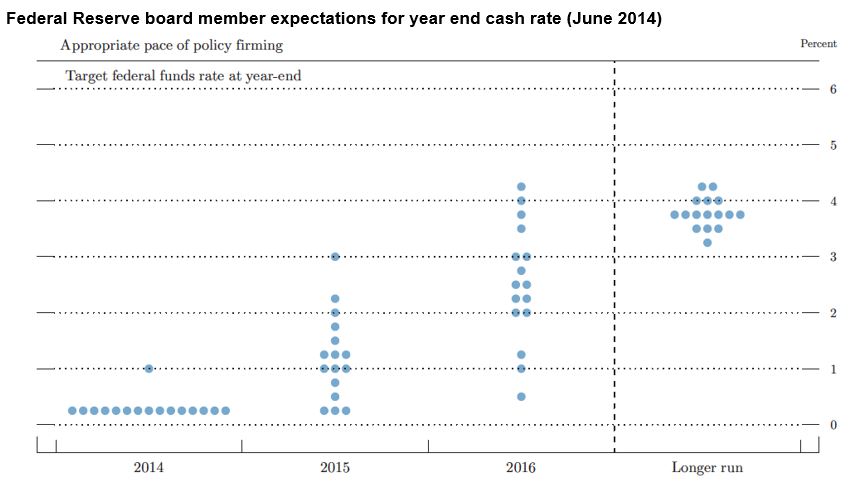

Even their cash rate forecasts tend to be wrong over time. The chart below shows the US Federal Reserve Board member cash rate expectations back in June 2014. The dots represent each member’s expectations for the future periods at that time.

So what this chart is saying is back in 2014 the US Federal Reserve Board members (who are actually in control of the cash rate) on average expected the cash rate by the end of 2016 to be c2.5% (it turned out to be 0.75%).

Federal Reserve board member expectations for year end cash rate (June 2014)

It appears market participants today still place great weight on these projections. Yet if they were fund managers, they would have been ‘binned’ by now.

The reflation trade has risks

We see the reflation trade as a consensus view across most financial markets. This can be dangerous – as the logic goes, “who else is left to buy?”.

But there are other risks that need to be considered.

- Academics are fast concluding traditional economic models that forecast inflation are inadequate. In fact, inflation is proving to be very difficult to predict.

- The US economy is not operating at full capacity. That is, based on employment / population ratios and capacity utilisation data, wage demands are likely to remain weak.

- Even if higher wages are to emerge, it does not follow this will lead to higher inflation. Fat corporate margins may absorb the loss – that is, wage / profit share may shift back to the owners of labour, more in line with historic norms.

- Those relying on central bank projections need to re-visit the track record of these banks.

- The assumed stimulus in the US is yet to be enacted. Failure to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (at the time of writing) has probably burnt some political goodwill and US Congress is still dominated by fiscal conservatives – so whatever is given by one hand, may be taken away by the other.

Despite all of these uncertainties, financial markets are running with the theme. After 25 years in financial markets there is one thing we have generally noticed – if it looks certain, it probably isn’t.

Disclaimer

The content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. The authors may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the article. The commentary in this article in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader. In particular, this newsletter is not directed for investment purposes at US persons.